Where: Deutsches Historisches Institut Paris

When: 20 to 22 November 2024

Application deadline: 1st December 2023

Organised by:

- Sarah Frenking (Universität Erfurt / Centre Marc Bloch)

- Christoph Streb (Deutsches Historisches Institut Paris)

- Mathilde Darley (CESDIP / Centre Marc Bloch)

- Anne-Emmanuelle Demartini (Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne / Centre d'histoire du XIXe siècle)

- Isabella Löhr (FU Berlin / Zentrum für Zeithistorische Forschung Potsdam)

- Roland Wenzlhuemer (LMU München / Käte Hamburger Kolleg global dis:connect)

We invite proposals for an international conference on the imaginary of 'dark networks' from the nineteenth century to the present that will take place at the German Historical Institute in Paris from 20 to 22 November 2024.

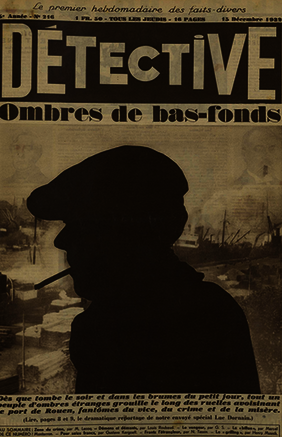

Modern imaginations of an interconnected world often have a 'dark' side. In the nineteenth century there was an explosion in enthusiasm for the opportunities offered by new forms of international communication, trade, and travel, the emergence of cosmopolitan ideals, or the urge for international cooperation. Yet contemporaries also imagined a dangerous milieu of vice and crime generated by illicit flows and populated by a dubious cast of shady characters. Anxieties over espionage, conspiracies and secret plots became a widespread cultural pattern. Since then, a sinister mythology has never ceased to captivate the modern imaginary: that beneath the real world lies a connected underworld made up of clandestine threads and movements that transcend borders and stretch across continents and oceans.

Contemporaries from the nineteenth to the twenty-first centuries commented on these 'dark networks' in various forms. Conspiracy theories, sensationalist media reports, popular fictional narratives such as novels or television shows, or reports and policy papers issued by international organisations, such as the League of Nations, claimed to offer insights into the global 'underworld'. The stories and images they produced were characterised by a series of stereotyped contrasts between high and low, transparency and secrecy, morality and vice, or day and night. They also mostly shared three typical components:

- 'Dark networks' consisted of specific figures such as drug traffickers, prostitutes, clandestine migrants, spies, vagabonds, freemasons, or anarchists. These figures were imagined to be well-connected and multilingual, transcending clear social and sometimes sexual categories. They also tended to be racialized and were often depicted in antisemitic terms. Portrayals focussed on profit-driven criminal operations beyond the reach of state control. The characters of the interconnected underworld were suspicious at best and a severe threat to the social order and political stability at worst.

- 'Dark networks' were also defined by specific spaces that denizens of the underworld moved through or resided in. These included typical liminal zones such as ports, borderlands, railway stations, or hotel lobbies, but also infrastructures like steamships, aeroplanes, or even tunnels. The result was an imagined topography 'below the surface', a burgeoning multiplicity of sinister connections and movements in the shadows of the modern world.

- Finally, 'dark networks' were perceived as crucial to enabling the circulation of specific goods like drugs, weapons, counterfeit money, reptiles, women, secret knowledge, or revolutionary pamphlets and ideas. Such goods had in common that they appeared contagious and harmful in case of unhindered circulation. They were therefore often imagined with particular features that enabled them to move under the radar or be smuggled across borders: for instance, they were encrypted, disguised, or hidden in secret compartments.

Most questions about images and stories of 'dark networks', however, still remain to be asked: By whom were they produced and what political and moral purposes did they serve? Which values, political systems, and (global) orders of property, race, or gender were they supposed to undermine? What explains their increasing or decreasing relevance for different societies between the nineteenth century and the present? And what does the idea of 'other' powerful, hidden, and dangerous networks tell us about global modernity in general?

The planned conference will explore the modern and recent history of images and narratives of 'dark networks'. It takes seriously the call to move beyond simplistic success stories of globalisation and contributes to the growing interest of scholars in its 'deviant' sides. To this purpose, it draws on existing scholarship on social imaginaries of crime, deviance, conspiracy, and espionage, and adds a transnational dimension to it. We would like to bring together contributions on different types of 'dark networks' discourses in order to interrogate their significance for understanding the ambivalences of global modernity and the construction and contestation of its social and political norms. In a chronology that spans the nineteenth to the twenty-first century, we are interested in discussing continuities and change in a transnational, long-term perspective. Proposals could, for instance, address topics and questions in one or several of the following areas of research:

1) Deviant globalisation. How can the investigation of imaginaries of 'dark networks' be used to tell 'another' history of global modernity? How did they interact with positive interpretations of transnational connections emphasising cooperation, communication, or civilisation? Could particular connections move from one side of the spectrum of light and dark globalization to the other depending on historical conjunctures? And how can stereotyped representations of shady connections be put in relation to the living conditions of actual marginalised people on the move?

2) Media spectacle and moral panics. How were images and narratives of shady connections used in crime fiction or spy films to captivate the attention of a wider audience? What was their role when investigative journalists created scandals and moral panics – and how did they spread across borders? Which psychological desires do representations of the global underworld reveal, and how was this 'other' exploited for political purposes both on national and on international scale?

3) Mystery, suspicion and 'truth'. Which particular mode of knowledge production does the search for hidden traces of sinister connections beyond official 'reality' reveal? Through what practical operations (some themselves transnational) were these alternative 'truths' of 'dark networks' produced? How can images and narratives of the transnational 'underworld' serve to better understand the production of the plausible, the credible and the verifiable in specific historical contexts?

4) Policing and regulation. How were representations of the global underworld used by representatives of states, empires and NGOs to introduce coercive measures – e.g. in the form of transnational police cooperation, border control, counter-espionage legislation, or moral reform campaigns? And which forms of gender, race and class discrimination were reinforced or produced based on images of sinister interconnections?

Modalities

We welcome contributions in English or French from disciplines such as history, sociology, literary studies, media studies, philosophy or criminology that focus on imaginaries of shady connectivity from the nineteenth to the early twenty-first century. Each proposal should include a tentative title, a short CV and an abstract of no more than 400 words. Please send these documents in one PDF file to sarah.frenking@uni-erfurt.de and cstreb@dhi-paris.fr by 1st December 2023. Travel and accommodation costs will be covered for active participants, subject to funding approval. The conference is planned as an on-site event.

» To the call for papers (pdf)

Bildnachweis: Détective 216 (1932), Ville de Paris – Bibliothèque des littératures policières.